28 Sep Hitting the ℮-mark: How Can We Make Sure All Kilograms Are the Same?

Hitting the ℮-mark: How Can We Make Sure All Kilograms Are the Same?

28 September 2022

To avoid underfilling pre-packages, many businesses risk overcompensating and adding too much product, which can have profound economic implications. Switching to the ℮-mark can help to improve accuracy, save money, and standardise the kilogram across Europe.

Strict market legislation ensures consumers are protected when purchasing pre-packaged goods: they can trust that the net quantity of product listed on the pre-package matches the contents inside. Yet too often, the concern of underfilling leads packers to overfill, sometimes by substantial amounts that over hours, days and weeks can add up to significant financial losses. And with fast-rising inflation increasing the costs of many goods, the processes and mechanisms that ensure accurate filling take on an extra urgency.

What measuring principles do packers use?

In countries like the Netherlands, packers use two different standards to ensure consumers receive the quantity of product they pay for. The first is the more traditional minimum principle, which dictates that net quantity can be more but not less than defined on the label. Pre-packages that fall below this nominal amount must be thrown away or reworked, hence why overfilling is preferable despite its cost inefficiency.

The second standard is the ℮-mark, or estimated sign, which indicates that the nominal quantity is equivalent to a product’s average weight per hour. An averages-based system allows weight distribution to better align pre-packages with the nominal quantity. Of course, there are limitations to this method, namely that the weight can’t be repeatedly lower than the nominal amount, and only a small percentage of outliers are permitted.

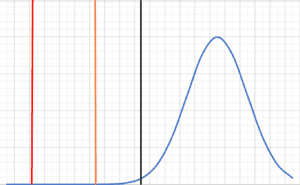

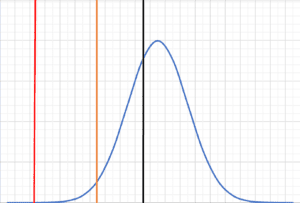

Take the below graphs: the left is based on the minimum principle, the right on the ℮-mark. If the black line represents the nominal amount, the red and yellow lines the lower limits, and the blue curve the variation in weight, the left graph demonstrates the narrow leeway packers get from using the minimum principle. In essence, any pre-package that falls behind the black line must be discarded. By contrast, the right graph shows how pre-packages can fall on either side of the nominal amount with limitations to prevent the weight from remaining too low.

The ℮-mark in practical terms

Understandably, consumers might look at the ℮-mark and worry that they’re receiving less product than before. In reality, only a small percentage of pre-packages (usually 2.5% or 2%, depending on the country) can fall between the red and yellow lines as marked above. Nonetheless, overfilling still occurs – though not to the same extent – because reducing the average to zero is not feasible. The ℮-mark is also part of European legislation, designed to standardise packaging measurements within the EU and facilitate trade between member states. At its most basic, it allows consumers in any one EU member country to trust that their 225 g ℮ pre-package of crisps contains, on average, the same amount as consumers in any other EU member country.

What’s more, supermarkets are increasingly requesting the ℮-mark on products sold in store, which could potentially lead to lost business opportunities for companies that fail to comply.

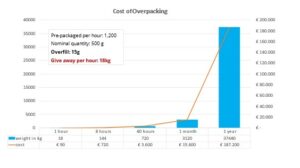

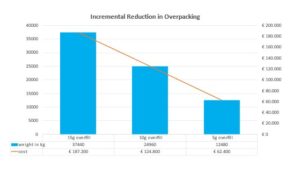

To expand upon the ℮-mark’s benefits when it comes to cost, consider the example from a meat processing company below.

The overfill figure may seem extreme, but it demonstrates the financial repercussions of not adequately managing product quantities in pre-packages. However, the above illustration does not suggest the complete eradication of overfilling. The ℮-mark also has its limitations: a certain overfill is still needed for many products, especially with a high distribution. Packers who do not overfill at all often have problems complying with the full ℮-mark requirements and end up having to reject a lot of pre-packages that inevitably fall below the lower limits. This costs even more money and produces more waste as both the packaging material and product must be reworked or thrown away.

Instead, illustrated below, a better understanding of filling processes and mechanisms inherent in the ℮-mark approach helps limit the amount of overfill and avoids unnecessary financial and environmental waste.

Pre-packages with quantifiable products – like oranges, for example – have a more noticeable overfill. With the minimum principle, if a bag of oranges was 2 g under the nominal quantity, then an entire extra orange would have to be added. But with the ℮-mark, it would be acceptable to leave the bag as is, if the average remains equal to or higher than the nominal quantity.

However, there are certain caveats. Regulating the weight of finer goods like coffee or flour is different to regulating the weight of more bulky products like pieces of meat which require additional considerations, such as the number of pieces included in each pre-package. Ultimately, packers must have an in-depth understanding of their filling processes and mechanisms, and it’s often more challenging than first appears: some packers, for example, will adjust their machines during production, making it harder to have a small weight distribution.

Want to use the ℮-mark? What next?

NMi is appointed by the Dutch government to evaluate the control processes of companies looking to produce under the ℮-mark. If their control system is adequate and their production follows the ℮-mark rules, NMi will advise the relevant authorities to formally recognise their system. We offer a full service to our customers deemed eligible for the ℮-mark, including a first visit to help them to set up their systems correctly and a second visit five months later to ensure that everything is running smoothly.